I really liked the video. It was entertaining, informative, and it really got at the heart of why I think everyong loves not only tricksters, but myths in general. They tell us about ourselves, they give us heroes (or anti-heroes, which I am a sucker for) to root for without taking on any of the risk ourselves. They tell us whats important to us as a culture, and they offer us an imaginative escape.

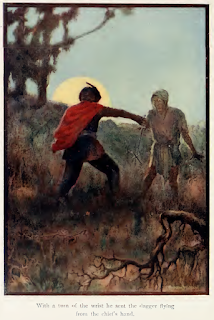

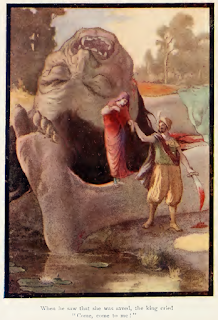

Anyway, tricksters, specifically, are popular for several reasons. They're usually the underdog, someone who is not known for having super human qualities. They aren't super strong or super fast, these are things that we normal humans know we'll ever be. But they're super clever, and that is somewhat attainable for us. Easier to imagine, certainly. Tricksters are known for being "agents of chaos," and their stories usually follow the model of them getting stuck in their own tricks but always getting away with it. Tricksters get their comeuppance...briefly...then it's back to scamming fools.

In a way, the way one sees a trickster is very revealing about their own personal philosophy. Someone who loves a trickster might say something like "Everything is legal if you don't get caught!" while someone who doesn't like a trickster might say "Well, he's gonna get his!"

But everyone loves a trickster! They're the ones who throw a wrench into the system, making them cultural heroes for the oppressed because they went against someone who clearly outmatched them and still got away with it! Like Brer Rabbit or Hermes. They're also culture heroes because their stories can be used to explain the invention of something that a society really relies on, like Loki and the enchanted boat, Odin's spear, and Thor's hammer. They're creative, inventive, and intelligent, and every culture in the world has some form of artistic expression and/or intellectual appreciation which makes them universal characters as well as culture heroes. Usually they portray moral ambiguity--which even the most pious of people have struggled with, which makes them relatable.

I think that the reason some people don't like a trickster is the fact that they remind us of our baser instincts. No matter how sophisticated we become as a species, we can't forget the fact that we're animals. I think that the Native emphasis on animal/human spirits and heroes shows this pretty well. The trickster is always motivated by the lowest of needs, even though he uses his higher intelligence to achieve his goals. Food, drink, sex, entertainment, greed...we don't outgrow base desires, they just get more sophisticated as we as a species becomes more complicated. A modern trickster might be motivated by political power, by money, by no-strings sex, by social media status...

I chose this video because I was going to do a portfolio project on tricksters. But thinking about "modern hedonism" gives me ideas for maybe writing a new trickster...I don't know. That's the thing about tricksters, they keep you on your toes.

|

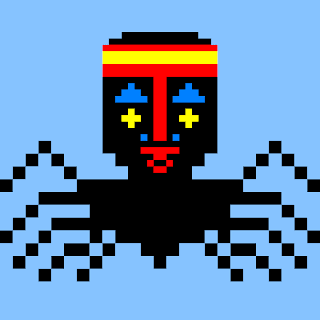

| Anansi - by mikkel via piq |